What if I want to know more, not less, about the English colonists who get celebrated this time of year?

A synthesis of my research, as a descendant of these people

It’s that time of year. A time to notice how normal a settler colonial worldview feels to me. A time to grieve, to give thanks, and to deepen my commitment to anticolonial work, to supporting Indigenous-led movements for rematriation where I live and across the globe.

I recommend listening to this episode of the Indigenous women-made podcast, All My Relations. Hosts talk with with Wampanoag scholars Paula Peters and Linda Coombs, who tell us the real story of Thanksgiving, from an Indigenous Perspective: “ThanksTaking or ThanksGiving?”

Along with the links shared in the episode notes:

Haudenosaunee Thanksgiving Address

Frank James Full Speech (Uncensored)

Full 50th Year Speeches at Cole Hill

More on Paula Peters: Re-Informed Mayflower 400, Mashpee Nine, Twitter

More on Linda Coombs: Dawnland Voices

Yesterday, I zoomed into the 4th annual webinar - Rethinking Thanksgiving: Colonialism is the Problem, Solidarity is the Answer - and I am awaiting the links to the recording and resources. I will share those too when I get them. It could not be more important to be making links from Turtle Island to Sudan to Palestine.

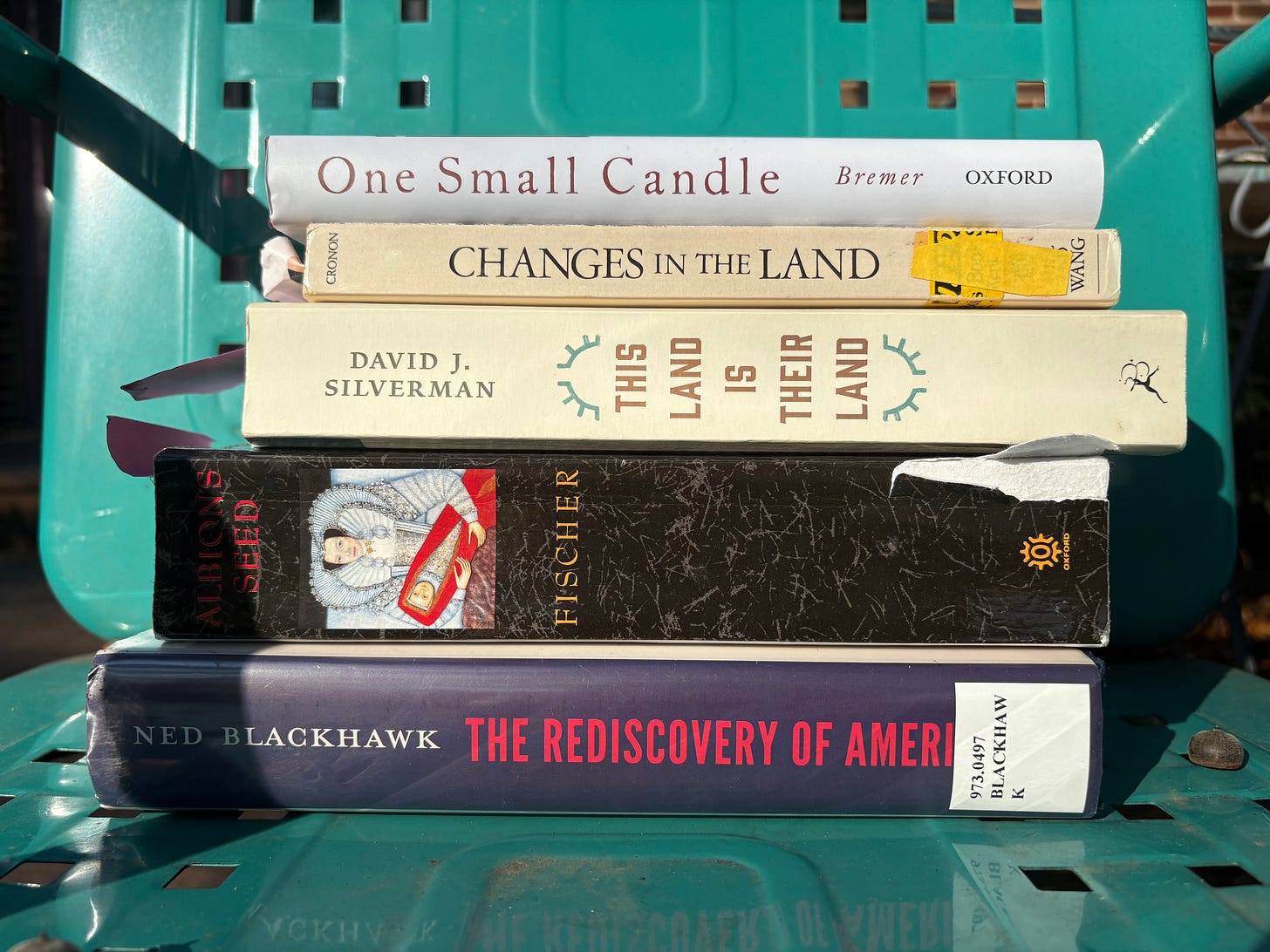

This year, I pulled out my stack of books on the English colonization of what is now called Massachusetts. I put together a synthesis of some of my research1 and here it is!

What would a true accounting by the descendants of these English colonists look like? To the lands and peoples of Turtle Island? For the harms of the 1600s and the centuries of settler colonialism since?

I’m not interested in throwing the Puritans into a “bad ancestors” bucket. I am interested in repair. Part of that is being honest and specific about who I come from.

I grew up knowing that some of the people I came from were the people who often get called ‘pilgrims.’

Supposedly, they dressed like this. [See photo above of a carved male figurine wearing tall black rimmed hat, black cape, black knickers with white stockings and black buckle shoes; female figurine wearing white and black bonnet, black shirt with wide angular white collar, and dark red skirt, holding a bowl of corn]

They were English people.

They were actually Puritans, part of a broad movement to reform the Protestant Church of England in the 16th and 17th centuries.

80,000 of these English Puritans crossed the Atlantic to settle on Turtle Island. The first hundred on the Mayflower in 1620.

The rest on 200 ships that sailed between 1629-1640.

This very short period has been called New England’s Great Migration.

My ancestors were not just on one, but on several of those ships.

This Great Migration was a religious movement of English Christian families who meant to build a new Zion in America. They were landed families back in England, they partnered with financial investors to make their relatively expensive journey across the Atlantic possible. They were refugees from England, as their religious practices were illegal at that time.

Most of them were motivated by personal spiritual striving--seeking a place to serve God’s will and be free of temptation.

Governor John Winthrop, a leader of this movement, chose Massachusetts Bay to settle in part because he believed that “God had consumed” the Indigenous peoples “in a miraculous plague.”

On Wôpanâank, the ancestral grounds of the Wampanoag Confederacy, the English Puritans claimed land, built a settlement and called it Plymouth.

Plymouth was just one of several English and European outposts forming across the Atlantic world at that same time.

In the Caribbean, these included St. Christopher, Barbados, Nevis, Montserrat, and Antigua. Barbados and later Jamaica became the most profitable colonies in the English empire, linked to the economy of New England.

Plymouth, the first European settlement in what would become New England, is where the romanticized meal took place in 1621.

Between these English people and the Wampanoag people who lived there already.

The Wampanoags had been dealing with European explorers on their shores since at least 1524.

The European mariners called “explorers” by historians were in fact slavers who raided the Wampanoag coast for years before the Pilgrims’ arrival, capturing people for sale to distant places of which they had never heard. The Plymouth colonists were no better, despite their claims to piety. They introduced themselves to the Wampanoags by desecrating graves and robbing seed corn from underground storage barns.

The story of the Puritans is only part of the story of how the English colonized Turtle Island.

Three more large waves of English-speaking people would migrate in the 1600s and 1700s. These were not Puritan families. They settled in Virginia, Delware Valley, and Appalachia.

I want a more full and accurate understanding of all of this. I want to learn more in community.

This is why I’m sharing some of my research now.

But where did the national holiday come from?

In 1863 President Abraham Lincoln declared that the last Thursday of November should be held as a national day of Thanksgiving, apparently in response to intense lobbying by Sarah Josepha Hale, the editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book.2 Hale believed the observance would foster unity amid the horrors of the Civil War. Before this, Thanksgiving had been a regional religious day of fasting in New England.

It was one thing for the people of Massachusetts to claim the Plymouth Puritans as forefathers and a dinner between “Pilgrims and Indians” as the template for a national holiday. For the rest of the nation to go along, the U.S. first had to complete its subjugation of the Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains and far West. Only then could the U.S. stop vilifying Indians as bloodthirsty savages and give them an unthreatening role in the national founding myth.

It was no coincidence that authorities began trumpeting the Plymouth Puritans as national founders amid widespread anxiety that the country was being overrun by Catholic and then Jewish immgrants cast as unappreciative of America’s Protestant, democatic origins and unfamiliar with its values.

And at the same time that a system of post-slavery anti-Black racial terror and apartheid was being built and enforced.

These English Puritans, and the myths that have been made up about them, continue to shape culture, economy, and nationalist identity in the U.S.

As an anticolonial student of theology, I want to know more about their worldview. And about the global context for their colonialism.

I want to know more, as a curious descendant of these people who seem both very strange and very familiar to me.

As we approach the 400 year anniversary of the Puritan Great Migration (2029), what if descendants of those English people came together to do something unprecedented, reparative, and needed?

What if?

What if a group of us, descended from English settlers, came together to study more of this history and take reparative action?

What if?

Sources:

The Rediscovery of America: Native Peoples and the Unmaking of U.S. History by Ned Blackhawk

One Small Candle: The Plymouth Puritans and the Beginning of English New England by Francis J. Bremer

Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England by William Cronon

Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America by David Hackett Fischer

This Land is Their Land: The Wampanoag Indians, Plymouth Colony, and The Troubled History of Thanksgiving by David J. Silverman

Toxic white femininity research to come back to at a later date

I am thinking about how a religious day of fasting has become essentially a secular day of gluttiny and entrance into a season of rampant materialism.

WHAT IF? I am a descendant of the Gaines family who entered through Virginia in the mid 1600s. For some time now, I have thought about trying to gather the many, many descendants of the Gaines brothers to do this kind of study. If you decide to move forward with this, I will do that research and outreach.